Ancient Egypt’s Ritual Chemistry: a proof that Ancient Egyptians Got High to Seek Transcendence Through Altered States of Consciousness.

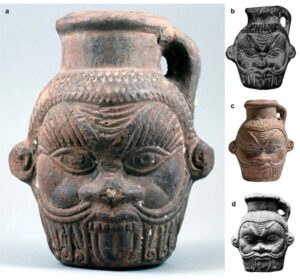

In a remarkable biomolecular archaeological revelation (https://shorturl.at/e3G7m) , a small Ptolemaic-era vase shaped like the dwarf deity Bes has opened a window into the mystic world of ancient Egyptian rituals. Found in the Tampa Museum of Art, the vessel contained residues of a fascinating concoction: psychotropic plants, honey, fermented fruit, and even traces of human fluids. These elements were no accident—they reveal an intricate ritual chemistry designed for profound spiritual experiences.

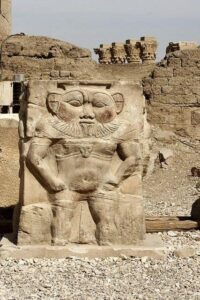

Bes, often depicted with a lion’s mane and a cheerful yet protective demeanor, was central to Egyptian household life. He was a guardian of joy, fertility, and protection, with a special role in childbirth and dream incubation. But his connection to rituals went beyond domestic life. Bes was often invoked in magical ceremonies, particularly those aiming to ward off evil or induce altered states of consciousness.

As protector of dreams, he carried out important oracular functions held during the Roman period at Abydos. In Ptolemaic times incubation rooms sprang up, called “rooms of Bes,” used for rituals of cure through dreams. Its association with wine is late, and we know a reference of the 3rd century BC about the existence of wine vessels called besiakon, on which this deity was depicted. We didn’t know what kind of drink was poured from these vases untill now!!

The scientific investigation employed cutting-edge techniques, from DNA analysis to proteomics, to identify the contents of this ritualistic liquid. Among the ingredients was Peganum harmala, Syrian rue, خرمل in Arabic or Besas in Syriac language (the plant of Bes) a plant known for its harmaline alkaloids, which produce vivid, dream-like visions. Harmaline’s effects were likely used in dream incubation rituals, where participants sought divine messages through prophetic dreams. The seeds of Syrian rue were known for their therapeutic effects, from pain relief to childbirth support.

Imagine a priestess or devotee drinking this potion in a sacred chamber, lying down, and entering a trance where visions of Bes or other deities offered guidance or protection.

Syrian rue connects intriguingly to ayahuasca, a sacred Amazonian brew used for spiritual journeys and healing. While ayahuasca traditionally combines the Banisteriopsis caapi vine (containing harmala alkaloids) with plants like Psychotria viridis (a source of DMT), Syrian rue seeds can serve as a substitute for the vine.

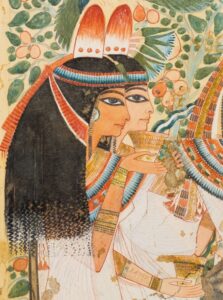

Another striking find was Nymphaea caerulea, the sacred blue lotus. Long associated with the afterlife and rebirth, the blue lotus was depicted in countless tomb paintings, often held by gods or humans as a symbol of divine connection. Mainstream Egyptologists and archaeologists often downplay the blue lotus in ancient Egypt, limiting its significance to a symbol of beauty, purity, and the afterlife. While it’s widely admired for its sweet fragrance and decorative use in tombs and temples, its potential as a tool for inducing higher states of consciousness is rarely discussed. Scientific reports, however, have shown that the blue lotus contains aporphine alkaloids, which can produce calming, euphoric, and psychoactive effect, creating a perfect blend with the visionary properties of Syrian rue.

Another striking find was Nymphaea caerulea, the sacred blue lotus. Long associated with the afterlife and rebirth, the blue lotus was depicted in countless tomb paintings, often held by gods or humans as a symbol of divine connection. Mainstream Egyptologists and archaeologists often downplay the blue lotus in ancient Egypt, limiting its significance to a symbol of beauty, purity, and the afterlife. While it’s widely admired for its sweet fragrance and decorative use in tombs and temples, its potential as a tool for inducing higher states of consciousness is rarely discussed. Scientific reports, however, have shown that the blue lotus contains aporphine alkaloids, which can produce calming, euphoric, and psychoactive effect, creating a perfect blend with the visionary properties of Syrian rue.

Why is this overlooked? Perhaps the reluctance lies in the discomfort surrounding the acknowledgment of psychoactive substances in sacred rituals, or the cultural taboo against viewing ancient Egypt’s spiritual practices as anything but symbolic.

For centuries, there has been a tendency to compartmentalize ancient cultures as “primitive” or “magical,” often dismissing the more complex aspects of their spiritual and psychoactive practices. Acknowledging that substances like the blue lotus might have facilitated mystical experiences could challenge long-standing perceptions of ancient Egypt as a purely rational and religious society.

Furthermore, the scholarly focus has traditionally been on physical artifacts and symbolic interpretations, often ignoring the biochemical realities behind rituals. The scientific understanding of psychoactive plants and their role in spiritual and religious practices is still relatively new, and thus, mainstream research often neglects to delve into this aspect.

As more interdisciplinary research emerges, involving not just Egyptologists but also pharmacologists, botanists, and biochemists, the blue lotus may eventually receive the recognition it deserves as more than just a decorative or symbolic element. Instead, it could be seen as a key to understanding the deeper, possibly psychoactive, spiritual practices of ancient Egyptian culture.

The presence of honey and fermented fruits suggests that this potion was more than just a psychoactive brew—it carried a sacred sweetness. Honey, often linked to the gods, symbolized life’s sweetness and immortality. Fermented fruit, likely grapes, may hint at the ritualistic use of wine-like substances, echoing Hathor’s myth, where she was calmed by a blood-red drink.

Interestingly, Bes’s association with rituals and intoxication isn’t new. He features in the myth of the Solar Eye, where he pacifies a furious Hathor with a blood-colored, plant-infused drink, saving humanity. Could the Bes vase’s concoction have been part of a reenactment of this myth? It’s plausible. Bes was known to bring joy, protect families, and guide individuals in spiritual journeys.

Adding to the mystique, human proteins—likely from fluids such as breast milk or blood—were also identified. These sacred contributions may have imbued the liquid with symbolic life-giving properties, connecting human and divine realms.

According to lead researcher Dr. Davide Tanasi, an archaeologist from the University of South Florida, the participants in this practice were likely ordinary Egyptian women seeking a divine intervention from Bes. These women may have hoped to conceive or safely navigate a difficult pregnancy. They would drink the psychoactive brew from a mug adorned with Bes’s likeness, then sleep, anticipating visions or guidance from the deity through dreams that could provide comfort or answers to their prayers.

This discovery transforms our understanding of Bes vases, which were often dismissed as mere decorative objects. Instead, they emerge as vessels of immense spiritual significance, blending biochemistry, mythology, and ritual practice. The ancient Egyptians were not just masters of stone and sand but also of the unseen forces that tied their world to the divine.

Such findings remind us that ancient rituals were as much about profound connection as they were about meticulous preparation. This sacred concoction was no casual mix; it was a recipe for transcendence, carefully crafted to bridge the earthly and the ethereal.

What’s most fascinating is how this discovery bridges the gap between mythology and science. The advanced techniques used—proteomics, metabolomics, and even ancient DNA sequencing—highlight just how much ancient Egyptians understood the natural world. Their rituals weren’t merely spiritual—they were alchemical, combining medicinal, psychoactive, and symbolic elements into a holistic experience.

The Bes vase discovery gives us more than a glimpse into the past; it’s a reminder of how deeply connected ancient Egyptians were to their environment and beliefs. With their mastery of natural resources and symbolic storytelling, they created rituals that resonated on physical, emotional, and spiritual levels—bringing together the seen and unseen worlds.

This Bes vase isn’t just an artifact; it’s a key to understanding a culture that sought connection with the cosmos through the artful interplay of myth, medicine, and magic.

References:

– https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-78721-8